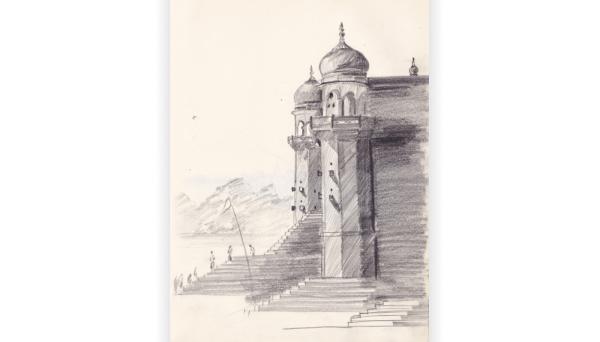

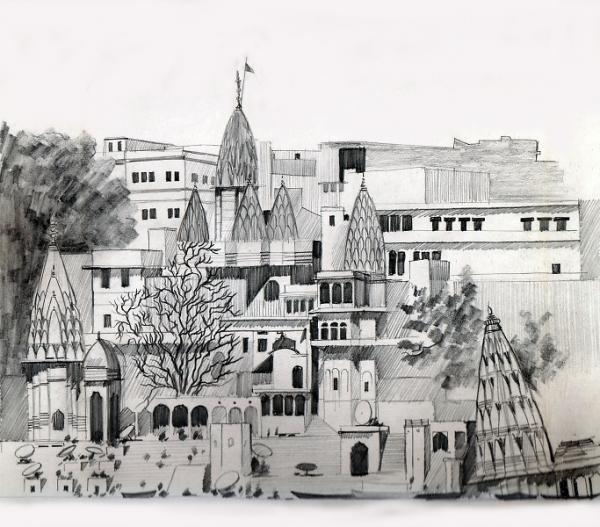

Chait Singh Ghat, pencil A4, 1978

The perfect painting

Associate Professor Peter Friedlander

Visions of Varanasi

What makes a painting of a place perfect? I’ve been wondering about this all my life, especially in relation to the city of Varanasi in India. I have sketched and painted this place since I first visited it just over 40 years ago in 1978. Varanasi is one of India’s most ancient and famous cities. At its heart is an old city of crowded lanes forming an arc along the bank of the river Ganga, considered one of the most significant rivers of India. For me it was also a special place, as it was where I started to learn Hindi and began to dive into the lived experience of Indian culture, civilisation and language. This first image is a sketch done on the spot when I first arrived in Varanasi.

Chat Singh Ghat, oil on board 24x36, 1982

I was immediately taken by the river shore and have been sketching and painting pictures of it ever since. For me this image, done some four or five years after I first visited Varanasi, is one of my most perfect paintings. Why is it perfect for me? Because seeing it evokes a strong sense of the time I spent there, reflecting, conversing and painting what I experienced.

The powerful memories of the people I met, conversations I had about life lived in the presence of an infinite expanse of light and water stretching out to the distant shore. To be in such a place soaking up the sights and sounds of an ancient civilisation was quite profound.

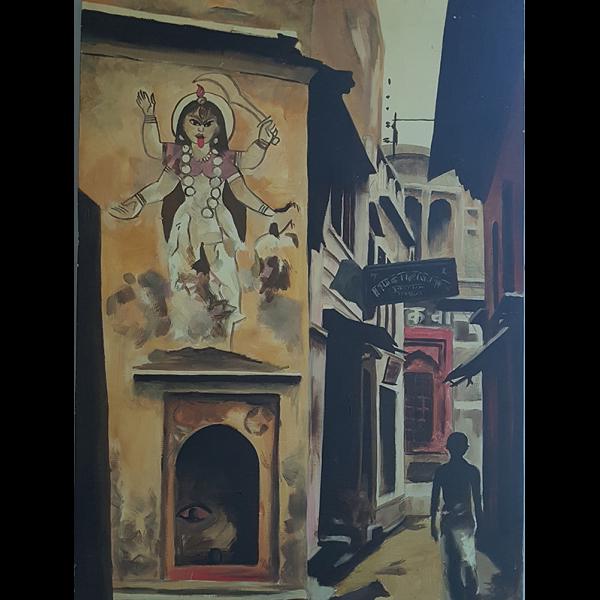

This picture for me is also a perfect image of Varanasi, which seems to suggest a contradiction. How can two pictures that are so different be of the same thing? On one level we could say that just like a coin having two sides, a place can be seen from multiple perspectives. Varanasi is as much the life lived in its ancient alleyways as it is the life on the riverbank. Both are distinctive characteristics of what makes Varanasi, Varanasi.

Another approach to thinking about this apparent contradiction is to consider what we really mean when we say ‘perfect’ in English. How might those ideas be related to how similar notions might be expressed in Hindi or Sanskrit?

Discussing this with Indian colleagues, we realised that translations of ‘perfect’ into Hindi often carried meanings that seemed at odds with English ideas of perfection. I was struck by the way some translations – like an everyday way to say perfect in Hindi, ek dam thik – meant something akin to ‘completely correct’. More abstract terms such as siddha, could be translated into English as ‘fully realised’. Both were only aspects of what we might mean by ‘perfect’ in English. As we mulled over this, my colleague, Ananth, recalled that to describe the deity Ram as perfect, it was said he was sarva guna sampanna, ‘replete with all [good] qualities’. I wonder if this is an example of how English uses ‘perfect’ in a wide range of contexts while Hindi and Sanskrit capture words and expressions according to the context.

Kali Charan Gali, oil on board 24x48, 1982

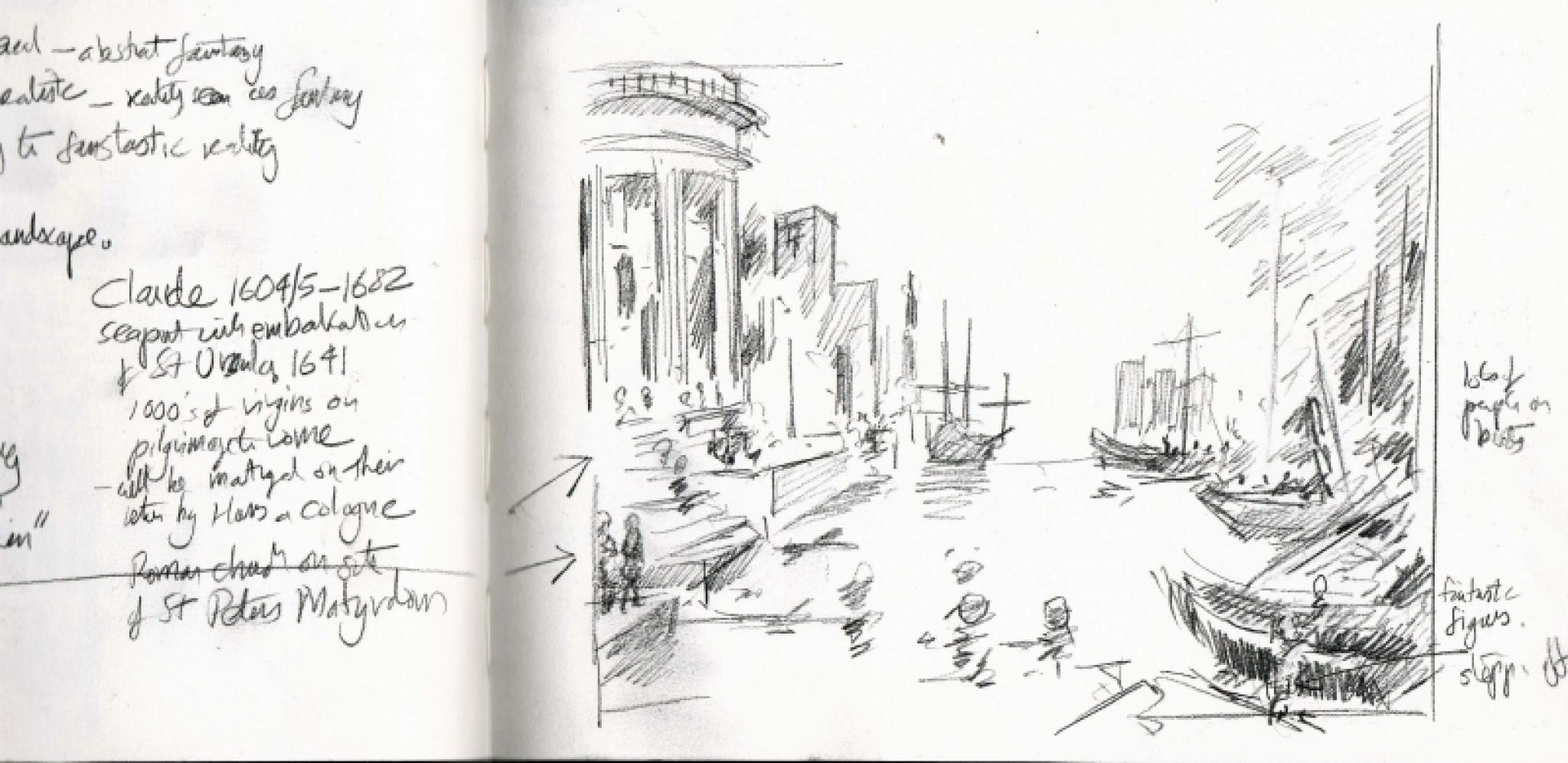

My sketch of a painting by Claude Lorrain, British Museum, pencil A5, 2017

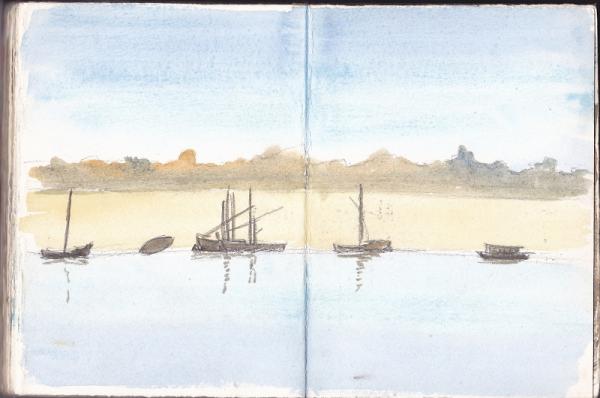

View across the Ganga, water colour 14x19cm, 1980

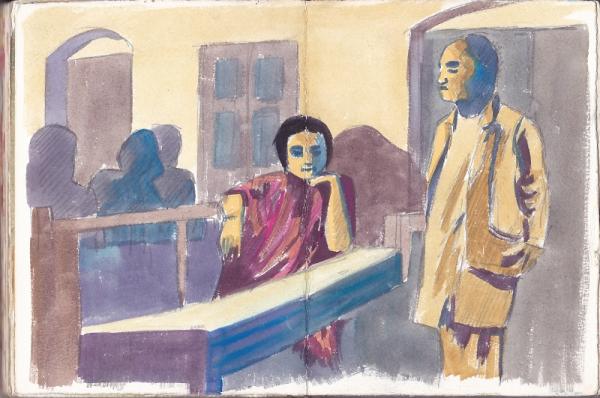

Krishna Mohan Singh and a student in class, water colour 14x19cm, 1980

Over time I have come to realise that when I was painting scenes of Varanasi, I was to some extent influenced by paintings I had seen of classical Italy when I was at high school, in particular the paintings of Claude Lorrain (1604/5–1682). In 2017, as I made sketches of some of his paintings in the British Museum, I could see that the way Lorrain had depicted imaginary seaports had influenced how I saw Varanasi. I was struck by the way his juxtaposition of classical buildings, boats and a theatrical cast of figures in diverse costumes, was a visual language that might have influenced how I painted. So to me the critical question is why did the perfect vision of the world in Lorrain’s paintings affect me so deeply?

I painted this sketch of the river from the window of my room. It is a very simple sketch, but somehow it reminds me of the light on the far shore and the boats moored there. Recently, I became interested in the idea that what makes a picture perfect is not whether it is a perfect reproduction of an external reality, but whether it has the power to convey moods, memories and reflections I experienced when making the painting. Now when I look back at my paintings of 40 years ago, it is as if they are a window into how I experienced the world then. So what makes a picture like this perfect, at least for me, is that it summons up a sense of place. For others, looking at this picture may evoke a sense of what it might be like to be transported to a Varanasi of their own imagination.

This painting below began as a pencil sketch drawn during a class and then I later added the water colour washes to it. When I look back on it, these classes were also a critical juncture in my life. I met Krishna Mohan Singh in a tea shop in Varanasi one day and, when he heard I wanted to learn Hindi, he offered to teach me in exchange for my teaching English in his coaching institute. So I ended up both learning Hindi, and learning how to be a language teacher. Looking at the painting, it transports me back into the classroom and how I managed to capture some of the ways in which people learn from each other and live within the spaces of the old city.

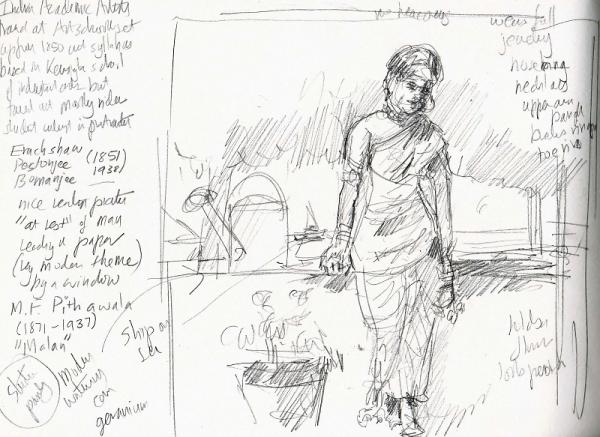

My paintings of India were shaped not just by Western ways of seeing India, but also by how Indian artists had shaped their own visual languages to represent India. When I was looking at Indian art in Delhi in 2017, it reminded me that developments like the arts and crafts movement and the Pre-Raphaelites had been influential in India just as they had been in the West. My sketch of this painting of a woman by MF Pithawala (1871–1937) had similar sorts of colours and folds as might have been found in a Western painting around this time.

My mother was also a painter, and painted scenes of life in Brittany in the 1930s. What I was seeing on the water’s edge in Varanasi, such as women washing clothes, my mother also saw in France 50 years previously. I think this is another element in what makes pictures perfect. Paintings are a perfect way to remember not just what individuals have seen, but how my family before me has seen the world. Perhaps a perfect painting can be a way to maintain a shared family heritage and community memory.

My sketch of painting called 'Malan' inthe Museum of Modern Art, Delhi, pencil, A5, 2017

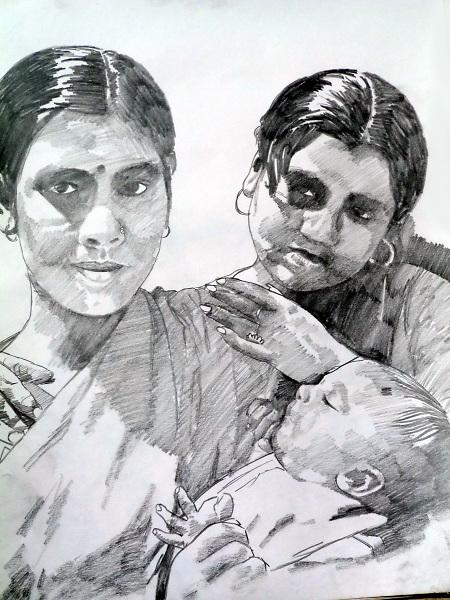

Sonu and Manju, pencil, A3, 1982

Time exists in an odd way in images and memories. The images seem to exist in a timeless realm, yet they are actually snapshots of frozen time. I lived with a family for a year or so, and in this drawing their neighbour Sonu is holding the middle sister’s newborn child while Manju, the younger sister, looks on. You can just see a black mark on the baby’s forehead. One of the fascinating things about drawing and painting is that it is also a support for conversation, and whenever I see this image, I recall all the conversations we had about why such practices were necessary.

In this case the black spot was to ward off the evil eye. So paintings are perfect supports for interactions with people, the artist and the sitters, and then become keys to learning about the culture and practices of the people in the images.

Sometimes I am asked why so few of my pictures show the burning ghats, the places where funeral pyres are lit. In a sense, the answer is simply that I didn’t like drawing funerals. What is more important is that people don’t like you drawing pictures of their family funerals. I did not feel it was a respectful thing to do.

However, this drawing, done from a photograph taken from mid-river, is of the main burning ghat. Actually lots of my drawings and paintings did include the places where the pyres were lit, but not while the funerals were taking place.

Manikarnika Ghat, pencil, foolscap, 1982

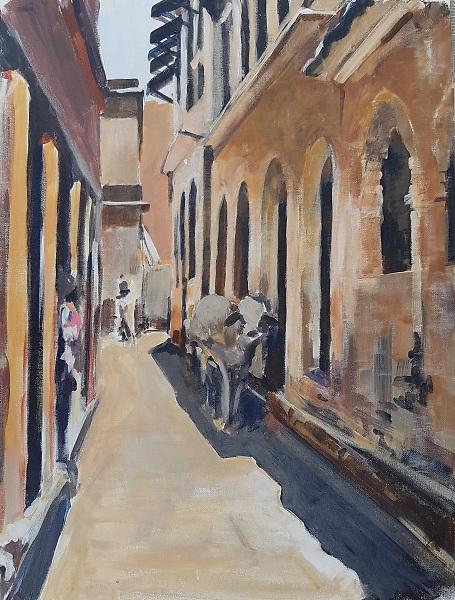

This painting was done in Singapore from a favourite photograph I took of Varanasi in the 1970s in an alleyway that seemed to me to epitomise the quiet beauty of old Varanasi. It points to another way in which a picture can be perfect, as it can be like an icon celebrating a vision of the world.

So in the end, what makes for a perfect picture? Perhaps for me, it embodies all the qualities of the original scene, while it may give other viewers a glimpse of a different world. In the end, creating a picture allows artists and viewers a space to interact together, and celebrate a shared vision of perfection.

Gali, oil on canvas, A2, 2008

Associate Professor Peter Friedlander first learned Hindi while living in Varanasi in the late 1970s before studying for a BA and PhD in Hindi and South Asian Studies at London University. His PhD was on the life and works of the medieval poet-saint, Raidas. He taught Hindi and Indian studies at La Trobe University from 1996 to 2008 and then at the National University of Singapore from 2008 to 2010. Since 2013 he has taught at ANU. His current research includes studies of Hindi education, Hindi literature and the relationship between language, society and religion.

All paintings and drawings by the author